By Shabbir Ajmal

The Baloch struggle against Pakistan’s military regime is neither new, nor imported, nor convincingly explained away by claims of foreign interference. It is a conflict with deep historical roots, one that reaches back to the earliest years of Pakistan’s existence. Yet Pakistani media outlets and security institutions continue to frame the unrest as an externally driven problem, frequently invoking Afghanistan as the hidden hand behind events in Balochistan. The historical record, political realities, and developments on the ground tell a very different story.

When Pakistan came into being in 1947, Balochistan was not simply another province waiting to be absorbed. It existed as a semi-autonomous political entity under the Khan of Kalat, who had declared independence and made clear his opposition to joining the new state. That resistance was short-lived. In 1948, Pakistan’s military entered Kalat and brought the territory under federal control by force. No referendum was held. No popular mandate was sought. The decision did not reflect the will of the Baloch population. From that moment onward, a pattern of mistrust, defiance, and prolonged confrontation took shape, one that has yet to fade.

Over the decades that followed, Balochistan has experienced repeated cycles of uprising and repression. Since 1948 alone, at least five major waves of resistance have shaken the province: the first armed opposition to annexation in 1948; the uprising led by Nawab Nauroz Khan between 1958 and 1959; another phase of armed confrontation from 1962 to 1963; the large-scale insurgency between 1973 and 1977 during the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto; and, from the early 2000s to the present day, a sustained mixture of armed and civic resistance.

Each episode has met the same response. Military operations, aerial bombardment, economic blockades, and political repression have followed with wearying consistency. The repetition itself is revealing. It points not to a purely security-driven problem, but to a political crisis that has never been seriously confronted.

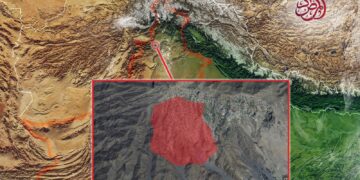

This unresolved tension is sharpened by the province’s extraordinary natural wealth. Balochistan sits atop the Sui gas fields, the copper and gold reserves of Reko Diq, and a coastline of immense strategic value. Its mineral deposits and geographic position make it one of Pakistan’s most resource-rich regions. And yet it remains its poorest and most neglected. Decisions about extraction and revenue are made in Islamabad. Profits flow outward. On the ground, many Baloch communities continue to live with chronic electricity shortages, unreliable water supplies, and widespread unemployment. For decades, this stark imbalance between what the land provides and what its people receive has fed a growing sense of grievance and political alienation.

Since the early 2000s, the conflict has entered a still darker chapter. Enforced disappearances have become one of its most haunting features. Thousands of Baloch youths, students, professors, journalists, and political activists have vanished. In some cases, their bodies later appear along highways, in remote mountain areas, or on deserted stretches of land, a grim pattern commonly referred to as a “kill and dump” policy. These practices have not only targeted armed groups; they have crushed civilian political activism and inflicted lasting trauma on families and communities across the province.

The story of Baloch resistance is also inseparable from the figures who have shaped it, political leaders, tribal elders, and intellectual voices such as Nawab Akbar Bugti and Khair Bakhsh Marri. Bugti’s trajectory was particularly telling. Once part of Pakistan’s political system, he was killed during a military operation in 2006. His death marked a decisive turning point, convincing many that even those willing to engage within the state’s framework were not beyond reach.

Throughout this long and turbulent history, Afghanistan is repeatedly introduced as a convenient explanation for events in Balochistan. Yet neither archival evidence nor contemporary reporting supports the claim that the conflict is directed from across the border. The Baloch movement emerged from within the province, developed in its own political and social environment, and continues to be driven by local dynamics. Afghanistan is neither a party to the struggle nor a sponsor of it, and there is no credible indication that Baloch leadership operates from Afghan territory.

What the persistence of resistance should offer Pakistan’s governing institutions is not another opportunity for deflection, but a moment of reckoning. Without an end to enforced disappearances, without genuine political inclusion, without allowing local communities a fair share in the wealth drawn from their own land, and without confronting historical wrongs rather than burying them, the cycle is unlikely to break.

Blaming Afghanistan does not change the past, and it does nothing to ease Baloch suffering. It merely diverts attention from the underlying realities inside Pakistan itself. And as long as those realities remain unaddressed, neither stability nor reconciliation is likely to follow.