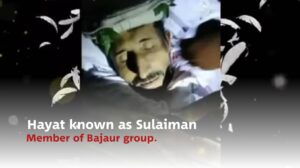

In Pakistan’s capital, Islamabad, a deadly attack was carried out last Friday (18 Sha’ban / 17 Dalwa) on a Shia mosque, resulting in approximately two hundred casualties. The so-called Islamic State (ISIS) claimed responsibility for the assault and also released an image of the attacker.

Just hours after the attack, Pakistan took the situation seriously and accelerated a series of operations against ISIS. According to sources, the group responsible for organizing last Friday’s deadly Islamabad attack is composed of members from the Dama Dola and Katkot areas of Bajaur in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

According to sources, the Islamabad attack was planned by Imran (known as Abu Bakr Bajuri), Idris (known as Yusuf), and Mullah Imran. These individuals directed the attacker, maintained telephone contact with him, provided him training in Bajaur, and transported an explosive vest for him from Peshawar. On the evening of the attack, Pakistan’s security forces conducted an operation against their base in the Hakimabad area of Nowshera, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, resulting in the death of Yusuf (Idris), the arrest of Abu Bakr Bajuri, and the escape of Mullah Imran.

Pakistani officials claimed that the attacker and the planners of the assault had traveled to and from Afghanistan in recent months, apparently to downplay their own failures in preventing the attack and managing ISIS elements within their ranks. In reality, all of the planners are originally Pakistani, and they only fled to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa—particularly Bajaur—shortly after the Taliban assumed power in Afghanistan, as the tightening restrictions there had made it impossible for them to operate.

It is worth noting that since 2023, this group has been involved in the killings of officials of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam party, religious scholars, and other prominent figures in Bajaur and Peshawar.

Maulana Salahuddin, member of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam; date of martyrdom: September 7, 2023.

Maulana Altaf Hussain, party member of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam and merchant in the Anayat Kali bazaar; date of martyrdom: September 7, 2023.

Maulana Noor Muhammad, member of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam and carpet merchant in Anayat Kali bazaar; date of martyrdom: June 22, 2023.

Moaz Khan, local official of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam and son of former Pakistani Taliban official Mufti Basheer (who was also martyred by ISIS last year during Ramadan); date of martyrdom: April 18, 2023.

Qari Ismail, Salafi scholar; date of martyrdom: October 29, 2023.

Qari Zain-ul-Abidin, Imam of Mosque; date of martyrdom: October 27, 2023.

Maulana Tila Muhammad, Salafi scholar and religious teacher; date of martyrdom: October 4, 2023.

Akram Khan, prominent businessman; date of martyrdom: November 9, 2023.

However, questions have arisen regarding why this group was not dismantled over the past two years, why operations against it were launched only a day after the Islamabad attack, and why Pakistan’s military strategy changed following the assault. These are the issues that emerged in the wake of the Islamabad attack, prompting intelligence analysts to offer a range of differing opinions.

Transfer of ISIS-K Leadership and Members to Pakistan

Following the Islamic Emirate’s takeover in Afghanistan, ISIS’s operational space was severely restricted. To ensure the safety and preservation of their personnel, the leadership of ISIS-K (Islamic State Khorasan Province) ordered the transfer of its members from Afghanistan to Pakistan.

Since ISIS operates on the belief that all governments are apostate and therefore subject to jihad, relocating to Pakistan posed its own challenges. However, for its political and intelligence objectives, Pakistan—indirectly and through a tacitly accepted arrangement—systematically accommodated the group’s leadership and members. The authorities facilitated their settlement in mountainous and peripheral regions of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, providing them with the infrastructure for military training and operational camps. Despite this, the group remained under continuous pressure and surveillance even in these areas.

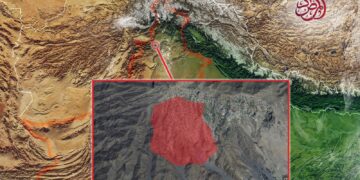

After establishing their bases in the Mastung area of Balochistan, ISIS resumed organized activities. On February 25, 2025, operations were launched against these bases, lasting three days. As a result, the camps were destroyed, and around 30 militants—including trainers, coordinators, and commanders, most of whom were foreign nationals—were killed. Among the key ISIS figures eliminated in these operations were Walid al-Turki, Mohammad Islam Kurd Irani, and Abdullah al-Turki.

After the Mastung bases were eliminated, ISIS shifted its focus to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. However, they were not able to remain secure there either. On November 26 of last year, a drone strike targeted their bases in the Jabarmela area of Khyber Agency, which were operating under the supervision of Abdul Hakim Tawhidi and Gul Nazim. On February 2 of this year, an unknown armed group attacked another ISIS base in the Shinko area of Qamberkhel, killing 11 militants and injuring three others. Among the deceased, all except three were foreign nationals. One significant local ISIS member, Adnan (also known as Abu al-Harb), was among those killed in this operation. Over the past two years, other ISIS members have also been killed in Pakistan by unidentified armed groups.

The Ideological and Political Anarchism of ISIS

ISIS is an organization ideologically fragmented due to its extremist beliefs, policies, and the absence of a unified strategy. Some members take takfir (excommunication) to extremes, exceeding even the group’s own doctrinal framework. They reject any distinction or gradation in issuing takfir and adhere to no concept of pragmatism. In contrast, others adopt a more pragmatic and strategic approach, even willing to cooperate with intelligence networks and follow their directives to ensure the survival of their group.

The presence of such divergent individuals within ISIS—whose ideological and operational approaches often clash sharply with those of other key members—has led to the formation of internal factions. Each faction elevates its own leader to near-idolatrous status, treating them as an Taghut (unquestionable authority.

Relations Between ISIS and Pakistani Intelligence

The history of the relationship between Pakistan’s intelligence agencies and ISIS-K dates back to the group’s earliest days. According to Sheikh Abdul Rahim Muslim Dost, in the initial stages of ISIS’s activities, Pakistani officers affiliated with Lashkar-e-Taiba attempted to bring the group under their control and use it to achieve their own objectives. Since then, ISIS-K and the Pakistan branch of ISIS have been exploited by Pakistani intelligence. A clear example of this is the targeted elimination of individuals in Pakistan who opposed the policies of the military regime.

Within the ranks of ISIS-K, most collaborators of Pakistani intelligence are fighters from the tribal areas along the Durand Line and from eastern provinces of Afghanistan who remained with the group’s initial leadership. Pakistani intelligence supports these individuals indirectly and assigns them objectives. However, in recent times, these figures have fallen out of favor within ISIS, lost their positions, and been replaced by new operatives who lack experience but adhere rigidly to ISIS’s original doctrine—which views all people outside the group as infidels and apostates.

Why Did ISIS Carry Out the Islamabad Attack?

Pakistan’s intelligence agencies maintain close ties with ISIS-K and the Pakistan branch of ISIS, including coordination and, in some cases, shared plans and objectives. As a result, ISIS attacks in Pakistan have taken on an intelligence-driven character, with their ideological, military, and political activities differing from operations in other regions. Within Pakistan, only specific targets—such as mosques, religious schools, ordinary civilians, prominent scholars, and public gatherings—have been attacked, in ways aligned with the country’s political conditions.

According to analysts of local armed groups, the intelligence-driven nature of attacks in Pakistan has led to growing suspicion, uncertainty, and mistrust within ISIS. In such an environment, the leadership of ISIS occasionally targets soft or symbolic locations, not to cause mass destruction, but to assert authority in the eyes of certain subordinates, secure the consent of key members, and boost the morale of their own personnel.

A study also indicates that the destruction of ISIS’s bases in Balochistan and the targeting of their new centers in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa dealt a severe blow to ISIS-K and the Pakistan branch of ISIS. The group felt the need to reassert itself, demonstrate loyalty to its ideology, and show independence from the influence of intelligence networks. As a result, they targeted a Shia mosque in the capital, Islamabad. This seemingly easy target allowed ISIS to make a visible statement, but they had not anticipated that such an aggressive move would come at a heavy cost.

Why Did Pakistan Change Its Military Strategy Against ISIS After the Islamabad Attack?

Following the Islamabad attack, Pakistan’s security agencies launched rapid follow-up and intelligence operations against the Bajaur faction of ISIS—far exceeding expectations. This demonstrated that Pakistan would no longer tolerate uncontrolled ISIS attacks, particularly those that conflict with the political interests and policies of the military regime. While attacks against Shia communities had occurred in various parts of Pakistan before, the military had not previously responded so swiftly against ISIS.

Islamabad, as Pakistan’s capital, is presented by the military regime to the world as a secure, well-developed, and symbolic city. Recently, Pakistan has been seeking foreign investment, aiming to show that the country offers a stable, secure, and law-abiding environment, backed by strong military and intelligence institutions. The Islamabad attack, however, threatened this narrative and the regime’s efforts, prompting a significant shift in Pakistan’s military strategy toward ISIS.

Initially, Pakistan’s military regime’s official propaganda outlets described the attack as a case of what they termed “Fitna al-Khawarij”. Typically, the regime uses this term for jihadist groups that oppose the military, rather than for ISIS or intelligence-linked militant organizations. However, when ISIS’s official news agency, Amaq, claimed responsibility for the attack and released an image of the attacker, it sent a clear message that ISIS had gained significant influence in Pakistan and established its presence there.

This development was unacceptable to the Pakistani military regime. To reinforce the seriousness and nature of the attack, they launched urgent follow-up operations, both to compensate for failures in intelligence management and, at the same time, to mitigate international criticism and concerns regarding ISIS’s presence in Pakistan.

It is noteworthy that, recently, Pakistani officials have sought to blame Afghanistan for deadly attacks. However, in the case of the Islamabad incident, not only the attacker but the entire group and planners were Pakistani nationals. According to sources, some relatives of the attacker were also detained by Pakistan’s security agencies.

The Islamabad mosque attack serves as a clear lesson for Pakistan’s intelligence apparatus: no matter how much direct or indirect support is provided to groups like ISIS to achieve strategic or tactical objectives, there will come a time when such groups turn against those who assisted them. This should serve as a wake-up call for Pakistan, urging the country to pursue a genuine and sincere fight against ISIS within its borders, rather than attempting to exploit them for its own purposes.