By Nauman Saeed

There is a bitter historical truth that many prefer to overlook: the collapse of a nation does not begin with the strike of a sword, but with illusion. It begins with a belief that quietly subdues minds before walls ever fall. This illusion persuades people that temporary concessions are wisdom, that peace with the powerful is salvation, and that abandoning the tools of strength is a small price to pay to “prevent bloodshed.”

Each January, this reality forces itself back into memory with painful clarity, marked by the anniversary of Granada’s fall in 1492, the final bastion of Muslim al-Andalus. That moment was not merely a historical tragedy or a sorrowful episode to be framed by the tears of Abu Abdullah al-Saghir, the loss of the towering palaces of the Alhambra, or the ruin of the taifa kings. It stands as an enduring rule: nations that accept promises of peace without possessing power soon discover that such peace becomes the very mechanism of their destruction.

This article seeks to demonstrate how the illusion of peace and hollow guarantees led to the loss of al-Andalus, and how the same pattern is now repeating itself in Gaza and, in a different form, in Sudan.

First: Granada and the Trap of “False Treaties”

Second: Gaza and the Trap of “International Guarantees”

Third: Sudan and the Trap of “Partition”

Conclusion: Military Strength Is the Language of Treaties

First: Granada and the Trap of False Treaties

Historical sources accepted by Muslim and Western historians alike, including al-Maqqari and Prescott, establish that the eight-century endurance of al-Andalus was not sustained merely by majestic architecture or intellectual flourishing. It endured because the defense of that land and its frontiers was understood as an existential obligation rather than a negotiable political choice.

When that consciousness gradually eroded, the logic of “managed retreat” entered the centers of power. Defeat was reframed as prudence, and continuous concessions were advertised as “clever maneuvers” designed to preserve what remained. The defense of Islamic territory was converted from a sacred responsibility into a political transaction. Perseverance and struggle came to be portrayed as reckless ventures or economic burdens that threatened stability, and in this way the value of jihad was subordinated to material comfort.

This trajectory reached its apex in the Treaty of Granada, where surrender was marketed as “minimizing losses.” The agreement was not simply a military capitulation; it was a psychological surrender to the logic of deceptive contracts. Isabella and Ferdinand issued what were presented as solemn guarantees to Muslims: freedom of worship, personal safety, and protection of property, provided that weapons were surrendered entirely.

History records what followed. Those guarantees were violated deliberately and systematically.

The tribunals of the Inquisition did not commence immediately. They began only after Granada’s Muslims had been fully disarmed and the victorious side had assured itself that resistance was no longer possible. At that point, sacred pledges were transformed into instruments of mass persecution.

Legal protections became pretexts for brutality, aimed at erasing Muslim religious and cultural identity. Hundreds of thousands were killed, expelled, or forced into conversion. These survivors would later be known as the Moriscos.

From a historical standpoint, this sequence constitutes unmistakable evidence that international assurances, or the sponsorship of any outside power, are worthless when confronting an adversary that regards one’s very existence as a threat. The purpose of Granada’s surrender was not the prevention of bloodshed. It was to create the conditions for the orderly destruction of its Muslim population. The illusion collapses here: weapons were not the cause of disaster. Disarmament itself was the disaster.

Second: Gaza and the Trap of International Guarantees

The tragedy of Granada is not confined to medieval history. It has become a blueprint now applied to Gaza with disturbing precision. Just as Andalusian Muslims in the fifteenth century were urged to relinquish their arms in exchange for “honorable pledges” and “religious protections,” Gaza today is being pressed, through certain Muslim states acting as intermediaries for the international community, Western powers, and the United Nations, to abandon its defensive capacity in return for promises of “reconstruction” and “permanent security.”

This trap rests on two central pillars.

Disarmament:

Proposals for civilian administrations or peacekeeping forces are presented as rational solutions, yet they echo Isabella’s ancient assurances. History teaches that weapons are the only guarantor that gives treaties substance. Once arms are surrendered, agreements become paper shields in the hands of executioners.

Delegitimization:

Casting the Islamic movement Hamas as an obstacle to welfare and stability mirrors earlier efforts to persuade Andalusian Muslims that resistance was the cause of their suffering, when in reality it was the basis of survival. Stripping resistance of moral and religious legitimacy by branding it “terrorism” is designed to sever Hamas from public support. The Moriscos paid for ignoring this lesson with blood and exile, and it must not be repeated.

Those who call on Gaza to disarm under the banner of ending violence are in fact preparing the ground for a modern inquisition. This time the destruction would be economic rather than judicial: starvation, siege, denial of the right of return, erasure of historical identity, and the seizure of land.

History demonstrates that enemies honor agreements only when they see force standing behind them. Diplomacy without military power is nothing more than an invitation to reenact Granada’s catastrophe.

Third: Sudan and the Trap of Partition

The calamity of al-Andalus did not begin with Granada’s capitulation. It began earlier, during the era of the taifa kings, when defense against external enemies gave way to internal rivalries, national strength was consumed from within, and foreign intervention was invited.

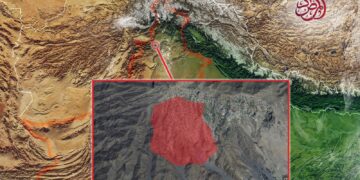

The same pattern now appears in Sudan.

Internal conflict weakens states and creates opportunities for external powers to intervene under the slogans of mediation and security. When national forces are exhausted, partition is imposed as the supposed solution. History does not isolate a single faction here. It reveals a broader law: nations collapse not only because of the strength of their enemies, but because of the damage they inflict upon themselves. Sudanese blood is being spilled by Sudanese hands, institutions are disintegrating, millions are displaced, and national forces are transformed into tools of regional and global agendas.

The outcome remains constant. The path toward foreign domination is smoothed. This vulnerability attracts foreign powers to Sudan’s strategic position and vast resources in gold, agricultural land, and water, fueling ambitions of exploitation.

Conclusion: Military Strength Is the Language of Treaties

The lessons of al-Andalus are not distant historical anecdotes. They form a warning map for the present, and their message is unmistakable:

• Weapons are the pen with which genuine treaties are written.

• Destroying defensive strength is not a route to salvation, but the architecture of subjugation.

Between efforts to disarm Gaza and the internal erosion tearing Sudan apart, al-Andalus speaks directly to the present: do not rely on the promises of those who regard your existence as a threat, do not surrender the elements of your power, and do not redirect conflict inward.

Nations that fail to learn from their defeats are condemned to experience them again and again, perhaps under different names, but with identical consequences.

The lessons of al-Andalus may be the final warning bell, urging recognition of priorities before regret becomes the only capital left behind.