By Salman Salim

The dispute between the Baloch and the Pakistani regime is one of South Asia’s longest-running and most deeply rooted conflicts, shaped not by sudden events or foreign intrigues but by decades of internal political choices and historical experience. Yet Pakistan’s official and semi-official media continue to push the story in another direction, portraying the struggle as the product of outside manipulation, most often pointing a finger at Afghanistan. These claims sit uneasily with what is visible on the ground and recur whenever attention turns to Islamabad’s own security and political record.

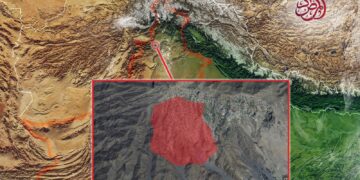

For years, Pakistani media have insisted that the leadership of the Baloch armed resistance operates from Afghan soil and directs the conflict from across the border. So far, those assertions have arrived without credible documentation, verifiable proof, or confirmation from independent observers. What can be established from available reporting and field realities points elsewhere. The central figures and decision-making structures of the Baloch movement appear to remain inside Balochistan itself, embedded in the same terrain and communities from which the conflict originally emerged.

The movement’s organization is sustained by the region’s geography, its tribal and social networks, and local backing rather than by foreign sanctuaries. References to Afghanistan function, in this telling, less as statements of fact than as political devices, deployed to relieve domestic pressure, obscure internal failings, and blur international perceptions so that Pakistan can step away from the heart of the crisis.

When the violence between the Baloch population and the Pakistani regime is examined without pretense, its principal causes come into sharper focus within Pakistan’s own policies rather than in the conduct of any neighboring country. Enforced disappearances, detentions without trial, sweeping military campaigns, bombardment of civilian areas, and the political marginalization of the Baloch have all played central roles in shaping the conflict’s trajectory.

Afghanistan did not set this struggle in motion, does not take part in it, and does not underwrite it. Kabul’s stance rests on a stated commitment to non-interference in the internal affairs of other states. Baloch leaders are not directing operations from Afghan territory, and the persistence of these accusations reflects political calculation more than established fact.

The durability of the Baloch resistance ought to push Pakistan’s governing institutions toward a reckoning with their own history, domestic strategies, and the long shadow cast by past abuses. Blaming Afghanistan or any other country offers no exit from the crisis and no credible path toward ending the fighting. It postpones difficult conversations and consumes time that might otherwise be spent addressing the roots of unrest.

Until Pakistan confronts the Baloch people’s demands for political rights, recognition, and human dignity, the conflict will not be defused by inventing external enemies. Lasting peace will only become conceivable when the problem is faced where it actually resides, rather than shifted onto someone else’s doorstep.