By Sayyid Jamal al-Din Afghani

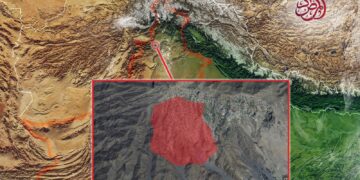

Overall, Pakistan has, from its very inception, been on an unstable course, constantly buffeted by waves of division and disintegration. At times, incidents arose in Swat; at other times, conflicts erupted in Balochistan and with the Khans of Kalat, followed by the separation and loss of densely populated regions like Bangladesh.

Despite all this, the failed policies of Pakistan’s ruling elite not only fostered resentment and dissatisfaction among the general public but also instilled a sense of weakness and self-doubt throughout society. Concurrently, skepticism toward Islamic teachings, religious values, and sacred symbols arose, shaped by the realities of these circumstances.

As a result of this situation, across the country some have initiated cycles of arson and destruction out of a sense of self-doubt, others have launched movements under the banner of defending Islamic values, and those who remain have, with great wisdom and insight, sparked a wave of intellectual awakening among the people.

Recently, at the Asma Jahangir Conference in Lahore, a remarkable and striking event took place. Sardar Akhtar Jan Mengal Baloch, a former and deeply insightful politician from Balochistan and one of the province’s influential figures, spoke with such heartfelt honesty and accuracy that it electrified the entire assembly.

At the beginning of his speech, he presented a historical document confirming an agreement between Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, and the Khan of Kalat. Sardar Akhtar Jan Mengal clearly stated that the agreement made between the Khan of Kalat and Muhammad Ali Jinnah has not been implemented even in the smallest part by the Pakistani state to this day; instead of honoring it, all its pages have been shredded.

In his remarks, Sardar Akhtar Jan Mengal also added that for the past eighty years, they have tried to cooperate with the state and continue a shared journey, but the government has always held them back. “My father, Sardar Ataullah Mengal, was elected as Chief Minister by the people’s votes, but the government did not recognize this decision. I myself became Chief Minister, but was removed from power through force and coercion.” He then mentioned several other individuals, stating that despite having popular support, none of them were granted their rightful representation.

All of this demonstrates that, despite all our efforts, the government has never been willing to walk alongside us, a fact clearly confirmed by nearly eight decades of history. For this reason, I want to repeat a statement once made by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to the leaders of Bangladesh: “You there, we here,” because there was nothing left for them to remain in. This statement carried even more weight in this assembly, as it implied that if the government is not ready to journey with us, it should at least recognize us as its neighbors.

It is important to understand that Sardar Akhtar Jan Mengal is considered a highly prominent, respected, and influential figure in Pakistani politics. His entire life has been spent in the political arena, and he inherited this vocation from his lineage, as his father was also a well-known and recognized politician. He is thoroughly familiar with all the intricacies, calculations, and complexities of politics and possesses complete awareness of the highs and lows of this challenging field.

Despite all this, he has grown so disillusioned that he is now suggesting recognizing Balochistan as a “neighbor” of Pakistan. Not long ago, Akhtar Jan Mengal even attempted, in his remarks, to create a kind of justificatory space for the armed resistance in Balochistan. According to him, the youth are unwilling to heed our words because they witness the state’s force, threats, coercion, and domination firsthand; therefore, he argued, we must go to them ourselves and become part of their resistance.

Here is another remarkable observation made by the renowned Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir. According to him, when Akhtar Jan Mengal raised the slogan of Balochistan’s separation during the Asma Jahangir Conference, all the participants present from Punjab and Sindh responded with enthusiastic and vigorous applause. The clear implication of this reaction was that the conference attendees supported Akhtar Jan Mengal’s stance.

Of course, Hamid Mir did not explicitly state what they agreed with, but the course of events makes it clear that when Akhtar Jan Mengal repeatedly spoke about state oppression, coercion, and the violation of agreements, all the participants were in agreement. This was because they had not only heard of these issues but had also experienced them firsthand, and some remained as eyewitnesses to these realities.

Hamid Mir also made another striking observation. According to him, after Akhtar Jan Mengal spoke, Rana Sanaullah, the Prime Minister’s political affairs advisor, addressed the audience. He condemned Balochistan’s push for independence and spoke about the possibility of harsh operations and civilian casualties. In response to this, participants began leaving the conference hall in protest.

The deeper meaning of this protest was clear: they were sending the message that “You cannot stop the oppression, coercion, and brutality that has exhausted the people of Balochistan to the point that they took up arms and retreated to the mountains. Yet here you are, issuing threats again. Therefore, we cannot accept this meeting or these statements.”

It is noteworthy that the protesting participants were from Punjab and Sindh. This indicates that even the residents of Punjab and Sindh are well aware that violence and brutality have been ongoing in Balochistan for a long time. In their view, the only viable solution to this crisis is to recognize Balochistan as a respected and sovereign neighbor of Pakistan.

Although waves of resistance emerge in various provinces of Pakistan due to state oppression and authoritarianism, manifesting as Baloch activism in Sindh, Saraiki movements in Punjab, and Hazara and other groups in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the problem in Balochistan has assumed the most severe form, accompanied by the highest levels of violence.

On one hand, there is armed resistance that casts a shadow of fear over major cities almost every day; on the other hand, prominent and influential political figures in Balochistan are increasingly exhausted and disillusioned with state policies, and are coming forward openly; and thirdly, even the religious community is gradually losing the capacity to keep their hidden grievances in their hearts.

In recent days, across various social and intellectual spheres, statements from religious scholars and spiritual leaders have been repeatedly heard, noting that at the time of Pakistan’s creation, Balochistan, then known as the State of Kalat, was an independent and autonomous entity. Its accession to Pakistan was conditional upon the implementation of Shariah law; yet today, after more than seven decades, not only is there no visible sign of Shariah, but even the little that once existed is steadily deteriorating.

Therefore, in their view, Balochistan must return to its original roots and reclaim its historical status. The clear positions expressed by people from all walks of life, political, religious, and social, indicate that Pakistan has reached the very edge of the dangerous chasm of division and fragmentation, and it is by no means unlikely that this pressure could suddenly erupt like a blaze.